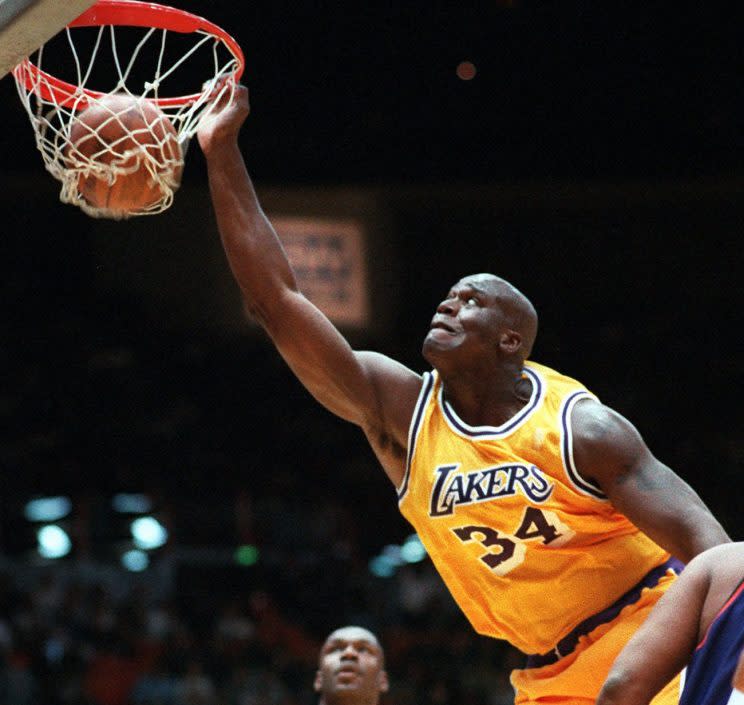

The riddle known as Shaquille O'Neal

When you covered the Lakers, you worked the parking lots, the parking garages, pretty much anywhere their cars were, because eventually they’d want to go home. That’s where I found Shaq one night, beneath Staples Center at the top of the ramp that led to a valet who would deliver Shaq’s car. Shaq stood beside one of his guys, a friend who performed critical duties like walking alongside him and laughing at his jokes and probably silly stuff, too.

The Lakers won that night against the Clippers, but Shaq and an unusually energetic Michael Olowokandi, the Clippers’ center, had jabbed and woofed at each other for the better part of two hours. Shaq was displeased. He hated when players he thought beneath him raised the courage to play him hard and pesky. Olowokandi, I can’t remember how or why, had at some point crossed that imaginary line, and Shaq was unhappy, and a win wasn’t enough to make him happy again.

He stood to the side of the tunnel, his hand at chest level inside his sport coat. His guy posed similarly.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“Get out of here,” he said.

“You waiting on Olowokandi?” I asked.

“You don’t need to see this,” he said.

“Dude,” I said, “if you’re gonna shoot Michael Olowokandi, I’m gonna watch.”

“Beat it,” he said, glowering.

I looked at him, he looked at me, and we both started laughing.

He didn’t have a gun. At least I don’t think he had a gun. They were playing, maybe even hoping to scare Olowokandi a little, because Shaq had a sense of humor that sometimes staggered toward kindergarten. Sometimes you’d have to work for it.

We called it “Shaq Surprise.” In a postgame scrum, win or lose, pissed at Kobe or not (usually pissed), Shaq would sit at his locker with his head down, gather up a question with a nod and then answer in a grumble inaudible from farther than three or four inches. So you’d get your tape recorder into that range, lob your question and watch his lips move. When his lips stopped you knew it was time to ask another question. If he tired of the same questions, as he did memorably once, he might grab hold of a beat writer’s collar with one hand, his pants inseam with the other hand, and hoist him straight over his head.

(Wasn’t me.)

“Stop asking me that,” he said, and there hung the beat writer, nine feet off the ground, clinging to his pen, notebook and tape recorder, everyone laughing except for the guy in imminent danger. One of the oddities of covering the NBA is you forget how big the men are, because they’re all big, and they look normal standing next to each other all the time. Then the guy you had a beer with the night before is clutching his work materials to his chest and waving his other three limbs frantically and you think not, “Geez, I hope he’s OK,” but, “Damn, that’s a large human being.”

Usually the interviews ended more amicably. You’d return to your desk, rewind your recorder to the point Shaq began mumbling, and only then discover what Shaq might have thought about beating the Kings, or watching Kobe shoot 30 times, or, say, Michael Olowokandi’s game, and often it was funny.

“Write what you see,” was his go-to line, which was code for, “I ran up and down the floor for 42 minutes and got eight shots, how the hell you think I feel?”

Only once did “Shaq Surprise” end with, “Hey! Put me down!” Loud and clear, a little squeaky.

He had hand signs for the media, two upside-down M’s he’d hold against his chest while he shouted, “Media!” like we were so gangsta. He otherwise didn’t have much use for us unless a message needed to be sent, and we’d be in the middle of the next incident, chasing it, stoking it, making sense of it, then deciding if this were the moment the grand Laker era of Phil, Shaq, Kobe, etc. – three parades in three years, a story a minute – collapsed. Usually it did not. Eventually it did.

What I thought about Shaq in those years – 2000-04, basically – was that he liked fame and fortune at least as much as he liked the basketball, and the latter was required for the first two to work, and then spring would come and those priorities reversed. He was generally suspicious of the media, and yet the deeper one dug on him the more of a human being you might discover. He bought the longtime equipment manager a truck. He hoisted Mike Penberthy to the rim in pregame layup lines, just so Mike could dunk. Always thinking about the little guy, you know?

Yeah, he groused at times, but I think he knew how good he had it, and we certainly knew how good we had it, even if that meant a couple hours a day in the parking lot. Never know what you might see out there.

More NBA coverage from The Vertical:

雅虎香港新聞

雅虎香港新聞